he advent of several regulatory initiatives in 2025 will make their impact on the wireless and communications industry. It is well-known and well-publicized that hacking and subversion of the communications infrastructure by bad actors continues to rise. The effect is experienced every day by consumers, public safety and services, defense, and by every sector of our modern society. The growing implementation of “connectivity everywhere, all-the-time” means that necessary measures must be taken to address security issues related to the design and testing of devices and their integration into networks. The actions by bad actors (for whatever gains they hope to achieve, monetary, civic instability, pilfering of design, etc.) mean that security precautions are now more necessary than ever.

There are many reported instances of cybersecurity weaknesses, and the industry and regulators are taking back the management of this space. In the U.S., the National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST) has been at the forefront of leading cybersecurity infrastructure protections. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF 2.0) is designed to support industry, government, and other organizations. CSF 2.0 is becoming well-organized and accepted. I liken the current efforts to the early 1990s when the goals and objectives of telecom mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) were worked out and are still working well today.

This article outlines recent and near-term cybersecurity protections that are being enacted in the U.S., Canada, the European Union (EU), and other jurisdictions. At the core, achieving a balance between effective cyber protection and free trade can present multiple challenges when it comes to finding common ground.

- EU Cybersecurity Act: Introduces an EU-wide certification framework for ICT products, services, and processes.1

- U.S. Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA): Provides a framework to protect government information operations against cybersecurity threats.2

- Health Infrastructure Security and Accountability Act: Sets stringent minimum cybersecurity standards and requires annual audits for compliance.3

NIST’s CSF 2.0 is a set of voluntary guidelines designed to help organizations assess and improve their ability to prevent, detect, and respond to cybersecurity risks. The CSF framework was initially published in 2014 for critical infrastructure sectors but has since been widely adopted globally across various industries, including government and private enterprises. The framework integrates existing standards, guidelines, and best practices to provide a structured approach to cybersecurity risk management.

So far, adopting the NIST CSF framework is voluntary, but it is increasingly being seen as a mandatory requirement in many organizations. Especially within federal government agencies, compliance with the NIST CSF is deemed mandatory for those vendors who wish to partner with those agencies. But more and more private enterprises are taking a strong stance to protect their operations against cyber exposure, balancing access with appropriate protections. Entities must continuously be vigilant against nominal hacking and vicious attacks and take appropriate measures to ensure immunity.

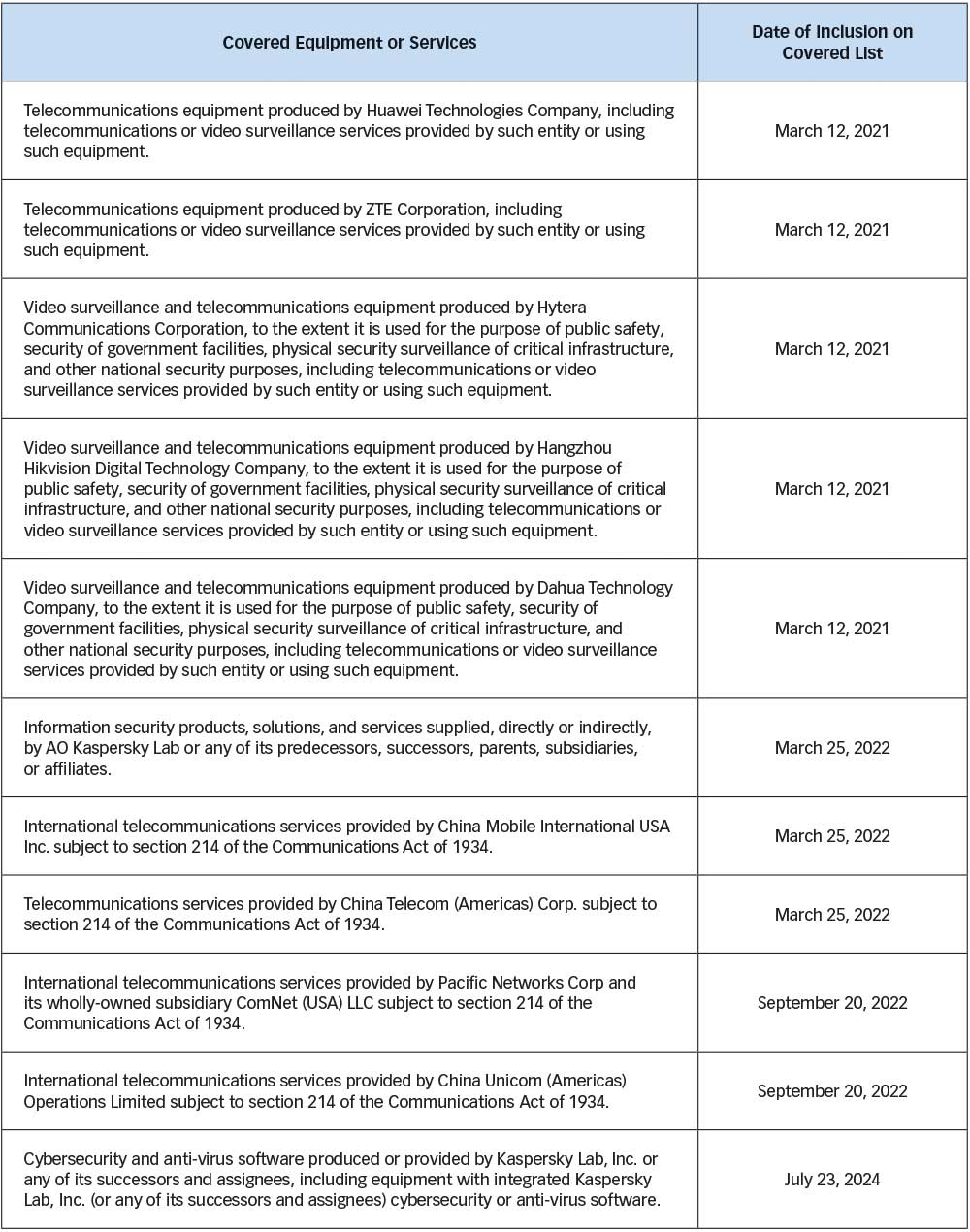

Toward that end, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has published a “Covered List” of such entities whose systems and devices pose a potential security threat to U.S. organizations. Published in August 2024, FCC document KDB 986446 D01 Covered Equipment Guidance v03, “Protecting Against National Security Threats to the Communications Supply Chain Through the Equipment Authorization Program,” details the names of entities that are deemed a “national security threat.” Almost all of these listed entities are based in the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The FCC’s Covered List is regularly updated to include additional entities and communications service providers who are banned from connecting their equipment to the U.S. communications network. A current list of these companies and their restricted equipment and services is found in Table 1, with a short description of their infraction and the date they were placed on the Covered List. The most recent addition is Kaspersky Lab, Inc., a Russian-owned entity based in Moscow.

The purpose of the Cyber Trust Mark is, again, to protect against compromising equipment that is exposed to the Internet. The program is still evolving, in real ways, but will ultimately lead to protections for the U.S. communications infrastructure.4

For the moment, the Cyber Trust Mark program is also voluntary but expect that to change as well. In my opinion, it won’t be long until this voluntary program becomes mandatory for device approvals. This is in step with the coming EU requirements for radio equipment under its Radio Equipment Directive (RED) and Cybersecurity Act, discussed in the next section.

What this means for device compliance is profound and must be considered for Internet of Things (IoT)-related devices that may be vulnerable (which is, to say, everything, from video systems to baby monitors to electric razors).

The FCC’s Cyber Trust Mark is shown in Figure 1.

These networks include, among others, cellular systems, local Wi-Fi, and something called LoRa (long-distance radio), which extends, in a sense, the connectivity of the Internet of Things (IoT) and other devices. In essence, the LoRa frequency ranges propagate farther than the Wi-Fi and cellular frequencies. This is handy for sensors and other communications implementations. The long-distance record for LoRa data transmission is now 1336 km or 830 miles!5

However, I digress. One can simply note that cyber protections address a sometimes-dizzying array of devices and technologies.

In addition to the EU’s RED, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) has taken steps to integrate cybersecurity protections into RED requirements, most notably its efforts to integrate supplemental measures related to cybersecurity. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/30 adds key changes to the requirements contained in Article 3.3 d/e/f of the RED, and serves as the basis for the EU’s Cybersecurity Act.

An August 1, 2025 deadline approaches for the updated RED requirements related to cybersecurity to come into force. There is a strong movement to comply, and opportunities await for multinational players to help the industry maintain their market access, which is difficult enough in the practical realities of global product approvals.

Article 3.3 e is self-explanatory but not always easy to follow. For example, how does a service provider or device manufacturer demonstrate that personal data is not subject to “spoofing.” In a practical way, this means solid fire walls and the education of operators and users so that they are not fooled by poaching attacks. And this is also tightly coupled with Article 3.3 f, which can occur if the proper protections are not imbued in the device design or the operation of the device.

Nonetheless, humans are subject to being “fooled,” and the best a device manufacturer or operator can do is to limit damage in some cases or have backups or built-in protections.

Evaluations of equipment and systems must include physical, data and protocols for “disaster recovery” which typically include some kind of risk assessment to ensure that procedures are in place to limit damage, physical or otherwise, from pernicious effects of the intent of “bad actors,” which can be domestic or foreign agents intent on disrupting or stealing from any manner of devices connected to the Internet, either directly or indirectly.

Eventually, these changes to the RED will affect broad areas of industry and nearly any internet device (connected directly or indirectly). This act affects large swaths of the industry and will be mandatory for information and communication technology (ICT) devices, which include just about everything.

- Oversight by government or regulators

- Internal policies

- Industry trends

This is extending into cyberspace, with its particular focus on the protection of networks, people, and personal information. The framework of the assessment is the same with the particular focus depending on the intent and content of the standard that is being assessed.

Many companies are taking matters into their own hands by requiring compliance with these ideals as a condition for working with them. It simply is what it is, and it is for a good cause. In any event, it becomes a business decision: if a company wishes to work in this increasingly complex space of interconnectedness, they must go through the actions, and it is not capricious. It involves a management-level decision to move the organization in that direction. The implementation of procedures affects all levels of an operation, from design to communication to inventory to supply chain verification.

This last point may be a little tricky because a vulnerability exists at the chip level. This is why suppliers on the FCC’s Covered List are suspect because it is conceivable, if not already happening, that malicious code can be embedded in the firmware of a microprocessor or other critical data part that can listen and report out activities of the user(s). For the integrator, there is practically no way to know this, and that is the difficult part for manufacturers who have wider goals and implementations of the technologies.

This goes right to the heart of the protection of IoT devices: “Someone might be listening…”

A success story: the EU and North America (at least for now) have mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) which allow for a free flow of goods across the borders. The MRAs include EMC and radio regulations that have worked very well for U.S. and Canadian manufacturers.

Yet this structure does not only affect U.S./CN/EU trade, but the approvals are often used for market access for other countries wherein the regulatory structure is not in place, or the regulatory structures have not matured and (depending on the size of the economy) may not be warranted. That is, these countries don’t need a full-blown regulatory structure and often rely on “CE Marking” or “FCC Certification” for placing products on the market.

These MRAs have been in place for EMC and radio equipment for a few decades, allowing access to markets under a combined mix of international and domestic regulations.

It remains to be seen whether the MRAs will include some of these new cyber provisions. For the moment, the FCC is requiring any entity that issues a Cyber Trust Mark approval to be located in the U.S. Reciprocally, but perhaps malleable is the EU, which is currently not recognizing Notified Bodies for cyber approvals outside of the EU. In effect, each country/economy is becoming more focused on protecting its own industries.

Perhaps this will change. But with the current political climate in flux at the time this article was written, it is hard to predict what the picture will look like in the near future or in the next few years. But as happens with most regulatory actions (and practically so), they are unlikely to be rolled back.

Whatever the final outcomes (and they are not static, mind you!) these frameworks are here to stay.

- “The EU Cybersecurity Act,” the European Commission’s webpage for the EU’s Cybersecurity Act, available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/cybersecurity-act (as of 4 May 2025).

- “S. 2251, Cybersecurity Act of 2023,” the U.S. Congressional Budget Office webpage for the U.S. Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA), available at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59481 (as of 4 May 2025).

- “Health Infrastructure Security and Accountability Act: A New Era for Healthcare Cybersecurity,” an article posted to the website of law firm JD Supra, available at https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/health-infrastructure-security-and-1139975 (as of 4 May 2025).

- Additional details about the FCC’s Cyber Trust Mark program are available at https://www.fcc.gov/CyberTrustMark.

- A comprehensive overview regarding the parameters of LoRa can be found at https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/docs/lorawan/regional-parameters.