ver the last 10-15 years, supply chain management has increasingly entailed addressing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues alongside the likes of quality, cost, service, and delivery. This has been experienced in the electronics industry, but equally the likes of the textiles and apparel, jewelry, automotive, and aerospace and defense sectors. Corporate practices have changed in light of campaigning by political activists and non-governmental organizations, as has legislation and/or government-backed voluntary initiatives.

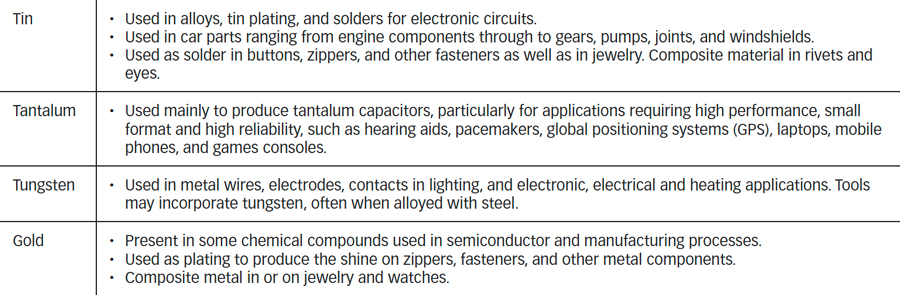

For those involved in the manufacture, distribution, and sale of electrical and electronic equipment, understanding conflict minerals – metals and minerals derived under duress and traded to keep armed groups funded – is likely best cast in terms of the wider identification, assessment, and management of ESG risks in supply chains (other risks might include, for example, child and forced labor, corruption and bribery, environmental pollution, etc.). While existing legislation may not apply to your business today, it might tomorrow.

Moreover, customers may have their own expectations and pressures can come from other actors like campaign groups and investors. This is emphasized early on in this article, especially as the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation does not presently apply to electrical equipment manufacturers unless they also happen to import conflict minerals into the EU – and in quantities that exceed specified threshold values. Even so, such manufacturers are a target of an EU effort to encourage voluntary disclosure on conflict mineral uses (on which, more below).

In turn, control of these resources and trade in them can become a political flashpoint and something fought over in civil wars. This was the case in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the First and Second Congo Wars entailed both the Congolese national army and rebel groups seeking control over 3TG mining, which encompasses many artisanal and small-scale mines.

- Determine applicability;

- Conduct country of origin inquiry;

- Establish a due diligence process;

- Determine status; and

- File a report.

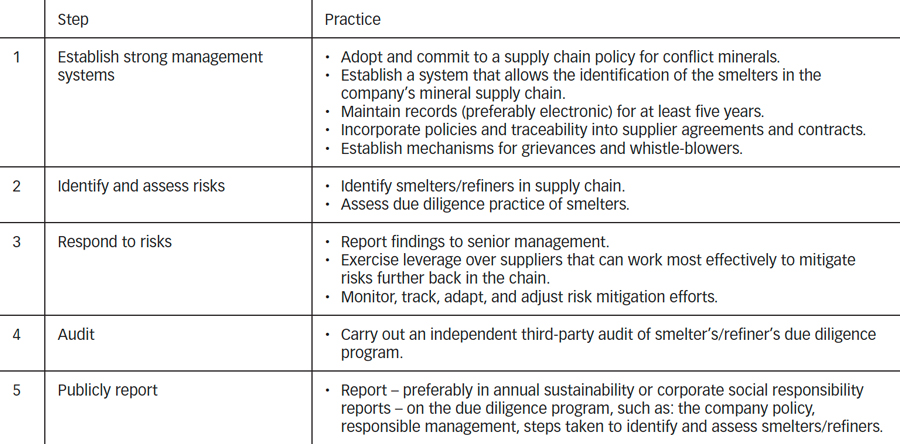

Regulation (EU) 2017/821 applies to EU-based importers of 3T ores and concentrates as well as gold above certain defined thresholds, as detailed in the Regulation’s Annex I. For in-scope importers, obligations span establishing suitable management systems, assessing and managing relevant supply chain risks, conducting third-party audits, and information disclosure.

- The EU Regulation does not impose any obligations upon downstream users of 3TGs, i.e., manufacturers of components or finished products, unless they also happen to be importing 3TGs into the EU. By comparison, U.S. legislation does apply in the downstream, with publicly listed companies that manufacture or contract to manufacture products that contain 3TG falling within the scope of the legislation.

- Unlike Dodd-Frank, the EU Regulation exempts small volume importers of 3TG by stipulating that the law “shall not apply to Union importers of minerals or metals where their annual import volume of each of the minerals or metals concerned is below the volume thresholds set out in Annex I.” 2 No such exemption exists under the U.S. legislation.

- The EU Regulation is more specific in defining what 3TG ores, concentrates and metals come within its scope. The Regulation’s Annex I gives a lot of detail, including Combined Nomenclature codes.

- Geographically, the EU Regulation is non-specific. Rather, the law concerns itself with 3TG sourced from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (CAHRAs) that might exist in the world. The U.S. legislation is specific though, applying only to conflict minerals sourced from the D.R.C. and its nine neighboring states.

Minutes from the 9 March 2018 meeting of this Group reveals that the compromise which saw Regulation (EU) 2017/821 “based on only importers of metals and minerals being covered by the legal requirements of the Regulation” entailed an expectation that “a series of measures also should be taken to retain the focus on and validity of efforts taken by downstream companies.” What, then, of these measures?

To register, business information including name and address, supply chain position (upstream/downstream), industry sector(s) in which the business is active, metals and minerals handled, and a summary account of due diligence practice appears to be anticipated. It would then seem that any more detailed information a company wished to share for online publication on ReMIS would be reviewed by a designated European Commission service desk. What this review would entail is, however, currently unclear.

A prototype version of ReMIS has been tested, with at least some industry stakeholders involved in this testing. This is reported upon in the 5 June 2019 minutes of the responsible sourcing Member State Expert Group, which notes that “the Commission received positive feedback on the usability and functionalities of the system.” However, it seems that safeguarding personal data is a concern, as is managing both European Commission and Member State Competent Authority compliance with requirements under the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Concerning this, the Commission has prepared an initial draft of a GDPR-required “joint controllership agreement,” but it is not known whether this has been accepted at the time of writing.

How, then, to prepare for this?

Many large, consumer-facing electronics companies whose products incorporate 3TGs have already taken significant strides in their management practices. Among them are Apple, Dell, HP Inc., and Intel. The way these companies have responded provides insight into how to manage and report upon conflict mineral uses in electronics supply chains.

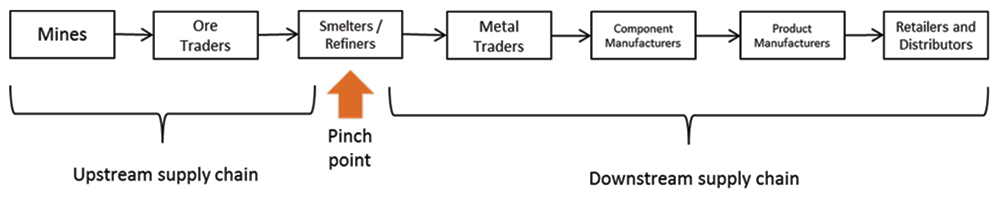

There is overlap in practice, which includes policy- and goal-setting, surveying suppliers, determining smelters in use, comparing smelters with those on approved lists (e.g., as published by the U.S.-based Responsible Minerals Initiative, RMI5), arranging smelter audits, and running awareness-raising training events. It is worth explaining the emphasis placed upon smelters here, and this is simply because they are perceived to constitute the pinch point in minerals supply chains (see Figure 16).

For practitioners, the following steps are advisable:

- Understand and scale the challenge facing your company. This is likely to include determining possible 3TG uses in products, then determining which suppliers you are going to engage with and how you are going to do this (e.g., by working up your own survey or making use of, say, the RMI Conflict Minerals Reporting Template7).

- Frame the company response, either with a new program of work or by expanding existing ones (e.g., programs for managing substance restrictions found in, for example, the EU RoHS Directive and/or EU REACH Regulation). Initially, this will be a top-level exercise anticipated to involve achieving senior management buy-in, securing a budget, documenting key policies and procedures, and determining roles and responsibilities for the likes of contacting suppliers and the collection, collation, and analysis of data. Cross-functional work is expected, so even if the program is owned and led by an Environmental or Corporate Responsibility Manager, the support of personnel from, for example, Procurement, Finance, and IT, should be considered, approved, and documented early on.

- Consider the optimal IT solution. This will depend on how many products and suppliers you are dealing with. If a large number, this will result in a lot of data, making a more automated (and sophisticated) solution desirable.

- Document as you go, including scoping decisions and other such judgements. This is good practice with regard to due diligence, constituting a record of key decision-making and reasoning deployed.

- Phase the program in, monitoring as you proceed. This provides scope for identifying problems and making corrections for better implementation overall.

- http://www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/mining.htm

- Note that, and as is explained in the Regulation’s Article 1(3), volume thresholds are set at a level to ensure that the vast majority of each ore, concentrate or metal targeted are implicated – and “no less than 95% of the total volumes imported into the Union of each mineral and metal under the applicable Combined Nomenclature code.”

- Accessible through the “Meetings” tab on the webpage of https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupDetail&groupID=3256

- Information comes from the presentation “The EU Regulation on responsible sourcing of minerals (“Conflict Minerals”): progress on implementation” given by Zora Mincheva, DG TRADE Policy Officer, to the RINA EEE & the Environment Conference on 14 November 2019.

- http://www.responsiblemineralsinitiative.org/smelters-refiners-lists

- Adapted from ChainLink Research, “Turning conflict minerals law compliance into a competitive advantage,” September 2013.

- https://www.conflict-minerals.com/solution/cmrt-512